AI? Sure. But it's still about competitive advantage.

LLMs, AI, machine learning, whatever you want to call it… it's still about competitive advantage.

Everyone's treating AI like it changes the fundamental rules of business.

It doesn't.

A successful business still needs competitive advantage — AI or not.

That's something many people seem to be forgetting in the current AI gold rush.

Competitive advantage boils down to this: earning more on your invested capital than it costs you to get that capital in the first place. In finance terms, that's earning returns on invested capital (ROIC) above your cost of capital (WACC).

Think of it like this…

There's financing available for manufacturers of flat-brimmed trucker hats at a cost of 10% per year. If you want to open up a flat-brimmed trucker hat manufactory (and of course you do), you'll need to earn ROIC above that 10% WACC, or you'll bleed yourself to death paying your financing costs.

Day 1: There are no flat-brimmed trucker hat manufacturers. Great! You can grab that 10% capital, start making hats, and charge basically anything you want (since people love flat-brimmed trucker caps). With limited competition, you price above cost and earn ROIC well north of your 10% WACC.

Life is good.

Day 30: Attracted by your outsized returns and the availability of that 10% capital, a bunch more manufacturers enter the market, all selling substantially the same product as you. Availability floods the market, everyone cuts prices, and returns fall toward WACC. You're still clearing the cost of capital, but just barely, and new entrants haven't stopped coming in. ROIC drifting to 10% is on the horizon.

Life isn't so grand.

Day 40: You get smart. You secure an exclusive 10-year licensing deal with Sesame Street and create a branded line of hipster Cookie Monster hats. Better still, you start using organic cotton and naturally advertise the heck out of that. Your costs go up — licensing and organic cotton — but now you have a differentiated product with legal exclusivity and brand equity that others can't copy. Lex Fridman buys one of your Cookie Monster hats and invites you on the podcast where you chit-chat for three hours about how special and unique your hats are. You now have a recognized brand that people will buy on the basis of that branding. You've built something defensible. Your pricing power and customer loyalty push your ROIC back above WACC, while some of the other manufacturers start to go out of business.

Life is good. Again.

That's differentiation

You've created distance between you and other providers of substantially the same good, allowing you to reap higher returns. Crucially, it's not just different; it's defensible — valuable, rare, hard to imitate, and embedded in how you operate. That's what sustains ROIC > WACC.

Every business needs to do this or there's really no reason to be in existence — and likely not much chance that the business will stay in existence due to competitive pressures and resulting squeezed returns.

It doesn't have to come from branded licensing deals or a high-profile podcast appearance that creates brand value. It can be a lot of things — efficiencies driven by scale, operational excellence, regulatory protections, unique access to a natural resource, patented product features, privileged distribution, proprietary data, and so on.

Vail Resorts has an advantage by way of unique, scarce mountain locations that confer pricing power. Walmart's advantage shows up in scale economics, vendor terms, asset turns, and working-capital discipline — thin margins, yes, but sustained ROIC above its WACC. Coca-Cola combines colossal brand, syrup economics, and a distribution system that delivers high ROIC over long periods. The signal of a moat isn't a fat margin in any given year; it's sustained ROIC above WACC.

Here's where AI and LLMs (don't) come in

So here's the thing about the current AI boom: An API from OpenAI, Anthropic, or Google (or heck, all three) isn't a competitive advantage. And having your people use a chatbot from one of said companies to accelerate their work, or getting your developers on one of those platforms to allow them to code faster… also not.

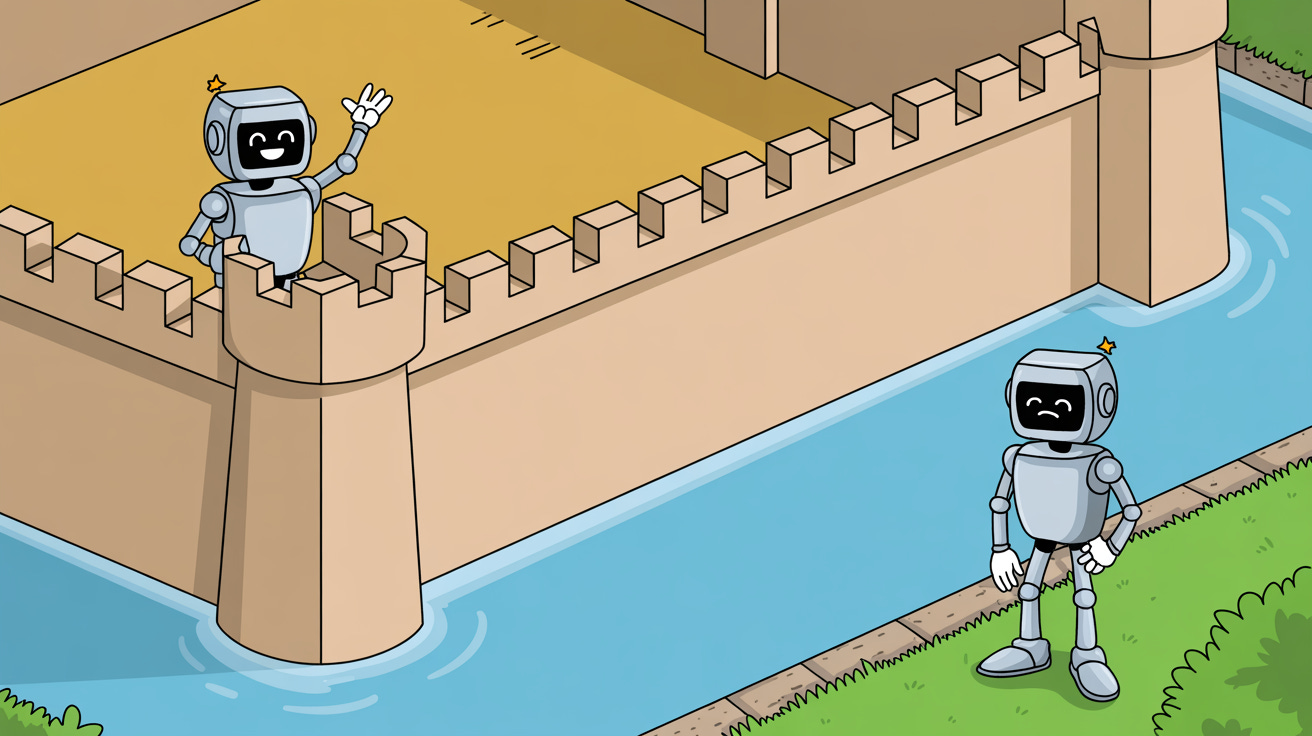

The problem here is that, yes, Business A can tap this technology, but so can Business B. At the same cost. At the same speed.

Business A's CEO says: "Glory days ahead people! The people we have on board can do more, do it faster, and do it better thanks to AI!"

All the while Business B's CEO says: "Umm, yeah, what she said. We have the same tools, and we're going to do all that fastness stuff too."

Now Business A and Business B are indeed running faster, maybe more efficient, maybe a lot more of a lot of things. But one thing neither has done is differentiate at all from the other.

But they have more plans! Business B's CEO says: "Now that we have AI and we can do more with fewer people we are going to let natural attrition run its course and shrink our workforce!" Business A one-ups by doing actual layoffs.

Both businesses do indeed end up producing the same amount with fewer people, earning higher profits for a bit until… Business C enters the picture.

Oh you didn't know? Business C has been doing all of the same. But Business C's CEO cares about nothing but market share (he’s a nihilist, Lebowski), so he does the unthinkable — cuts prices to gain an advantage on Business A and B. He can do that because unit costs have fallen thanks to the AI-driven efficiency.

And because no one has gained any real competitive advantage by piping in widely-available technology, Business A and B both have to follow suit, cutting prices, and eating away at those layoff-induced returns. In a market of near-identical offerings, that's classic Bertrand competition. If A or B had switching costs, capacity constraints, or brand power, this race to the bottom would slow. But as posed, they don't — so it doesn't.

Enter econ 101

Basic economics tells us what happens when everyone gets the same productivity boost. In the canonical framing, output is produced with capital and labor, scaled by technology: Y=A⋅F(K,L). Technology is the A — total factor productivity — the Solow residual. When A rises, you get more output from the same inputs. That lowers unit costs, which puts downward pressure on prices, which increases demand and expands output. Expansion then requires more inputs (capital and labor), even as the economy becomes more productive.

In other words, technological change on this scale does not, by itself, create particular advantages for singular firms; it lifts the productivity function for everyone with access. Much of the gain shows up as consumer surplus unless you have a moat to keep some of it.

What this means for our story is that technological change — in this case the explosion of AI/LLM usage — doesn't automatically translate into advantage for any particular firm. It's going to be pervasive across firms and produce widespread productivity advantages for the economy. Firm-level advantage accrues to those with scarce complements — proprietary data, distribution, brand, regulatory position, and the organizational capability to redesign processes — not to those who simply wire an API into a workflow.

Bringing it all together

We started with competitive advantage. We moved on to our A, B, and C businesses that were unsuccessfully trying to beat each other using LLMs. Then we got into the production function and how economy-pervasive technologies play into that.

So where does that leave us when it comes to LLMs and business use of them?

Back at competitive advantage.

Having a solid, durable competitive advantage allows a firm to earn ROIC above its WACC. Using LLMs, machine learning, AI, whatever you want to call it, doesn't by its nature give anyone a competitive advantage.

Then what's the big deal?

It's this:

It's going to be table stakes. New technologies that raise productivity lift all boats across an industry. They'll also sink the boats that don't adopt — they can no longer compete on cost, speed, or quality.

Speed matters, differentiation matters more. While AI usage doesn't automagically create competitive advantage, faster adoption can create a short-term edge. More importantly, differentiated use is an opportunity to create durable advantage: build with proprietary data and closed feedback loops, embed the tech into core workflows to create switching costs, leverage your distribution and brand, and lock in rights others can't get.

Look for new revenue streams. New technologies, while they displace workers and can wipe out parts of industries, also create new industries and new opportunities for entrepreneurship within firms: extending core capabilities into new revenue streams that weren't feasible before.

If you're a business leader, that gives you a playbook. Following point by point:

You need to be incorporating AI in meaningful ways to take advantage of its efficiencies. Your competitors will and refusing to is going to leave you lagging behind and at risk.

Implementation strategy is everything. For better or worse, you're stuck needing to implement this in ways others are. But if you can figure out ways to implement this in ways that others aren't and, ideally, in ways that others can't copy — leveraging proprietary data, internal expert knowledge, privileged distribution, exclusive rights, and embedding it into the fabric of your workflows — this can be a chance to create a source of competitive advantage.

Don't reflexively pass all the gains through to customers. Price with intent — value-based, metered, or bundled — so you actually keep some of the surplus your capability creates.

Consider new opportunities this creates for your company to create new streams of revenue that weren't possible before. This doesn't mean a restaurant group starts training models — that's silly. It does mean extending core capabilities into new business lines facilitated by AI.

LLMs are a general-purpose technology. They will be everywhere, and that means they're hygiene, not a moat. Competitive advantage comes from what only you can combine with them — your data, your distribution, your processes, your brand — converted into ROIC above WACC. Adopt fast, differentiate faster, and keep some of the surplus.

Lex can have a hat; you keep the economics.

(Ok, get one of the hats too, they sound amazing)